![]()

![]()

November 2003

WHO IS THE BOY IN THE BOX?

In 1957, a young boy was discovered dead in the woods in Fox

Chase, his head poking

from a cardboard box. It would become Philly's most famous

and baffling

unsolved murder. Forty-six years later, long-retired

investigator Bill Kelly is

on a quest for answers.

By SABRINA RUBIN ERDELY

|

|

|

Photograph by Steve Belkowitz |

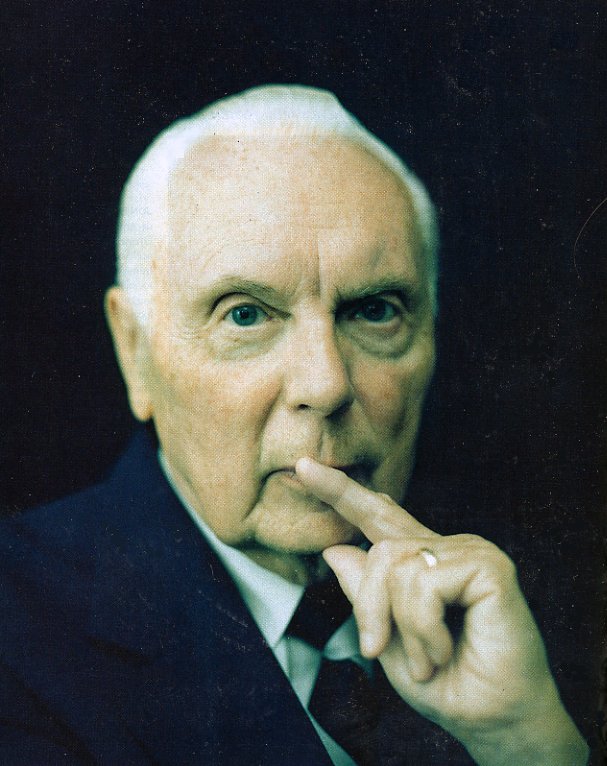

An old man sits on an

aqua couch in a pink room. Soon he will visit a little boy's grave. But first

he leafs through the white binder in his lap, turning its plastic pages with a patient

hand. Here is the typewritten autopsy report, dated

The little boy would be

50, 51 years old if he were alive today, but in Bill Kelly's mind he is still a

child. Time has stood still for the boy, but not for the man. He has

circulation problems now, and age spots on his skin, and white hair he combs

neatly back each morning, and a plastic pillbox of medicines he takes daily,

some with food, some on an empty stomach. He's been living on God's green earth

for 75 years. He's seen a lot during that time - some of which he'd rather

forget, frankly - and yet Kelly remains singularly by this case, by this one

little boy, who has been on his mind for the better part of 46 years. It's the

one case he couldn't close, the one mystery he couldn't solve. Kelly knows time

is running out. He leans in to study a close-up of the boy's face for the

umpteenth time. Who are you? he wants to ask. What is your name?

Time to go.

The ridges of the little

boy's footprints are burned onto the insides of Bill Kelly's eyelids. Kelly can

see them clearly, can fix the image so he can zoom in on the loops and whorls

that pattern the boy's flesh. It's like standing next to a painting on the wall

and peering closely enough to make out the individual brushstrokes - the

elements of creation. But take a giant step back, and the whole picture comes

into terrible focus. The four round bruises stipling the boy's forehead. Blue

eyes whose lids have fluttered partly open, as though the boy were waking from

sleep. The small, dry lips parted and crusted with blood. Tiny ribs like

chicken bones etched through the skin. The little tummy already greenish with

rot.

That February day in

1957, 29-year-old fingerprint expert Bill Kelly had lifted a little foot from

the metal gurney and examined its sole. Sometimes it's easier to step in as

close as you can, to concentrate on details so small that you don't see the

larger picture at all.

The boy had been found

hours earlier. A

The little boy was 40

inches tall and just 30 pounds, with a full set of baby teeth, putting him

between four and six years old - he was so malnourished, it was hard to tell

his age for sure. His nude, badly bruised body was wrapped in an

Indian-patterned blanket of rust and green. His blond hair had been recently

cropped in a homemade crew cut; his torso was dusted with the clippings. Other

than that, his body was clean; his nails were trimmed. The skin of his right

hand and both feet was pruny, as though they'd been immersed in water

immediately before or after death. There were surgical scars on the boy's ankle

and groin, and an L-shaped scar under his chin. The chilly weather had

preserved the body somewhat, but he'd been dead long enough - from three days

to two weeks - that the pull of gravity had sunk his eyeballs back into their

sockets.

By the time Bill Kelly

arrived at the morgue, the entire police department was talking in low voices

about the discovery. They were normally stoic guys, men of few words, most of

them vets who'd served in World War II or

|

|

|

A LONG VIGIL: Bill Kelly in his dining room. |

Kelly methodically set

his inks and rollers on the morgue table. He'd seen dead children before, in

For now, though, Kelly

was first and foremost a fingerprint expert, a coolheaded man of science and

reason. He inked the little boy's fingertips and feet and pressed them onto

paper. Someone would come forward to claim this boy; of that, Kelly and the

police were certain. The case would no doubt be solved by Monday morning.

Bill Kelly steers his

silver Grand Marquis westward from Northeast Philly, toward the boy's grave.

His hand rests lightly on the wheel; the insignia on his gold Knights of

|

|

|

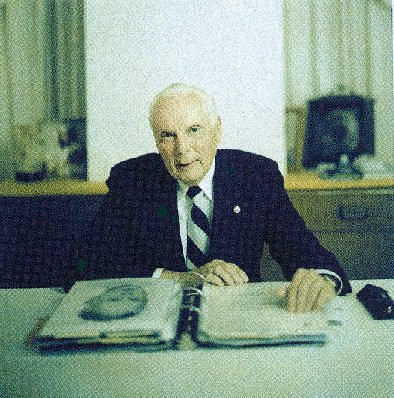

The flyer that flooded the region in 1957. |

The boy's discovery

created a nationwide sensation once an alert was broadcast to all 48 states via

police teletype; headlines dubbed him "The Boy in the Box." Locally,

the case was inescapable, with 400,000 flyers of the boy's likeness printed up

courtesy of the Inquirer and handed out on street corners, hung in shop

windows, enclosed with every gas bill. Hundreds of leads came in. A

The leads soon fizzled,

baffling police. It seemed impossible that no one would recognize this boy and

come forward - no relative, no neighbor, no teacher, playmate or doctor.

Investigators redoubled their efforts. They ran an article in a pediatric

journal describing the boy's surgical scars, but got no response. They figured

out that the box originally held a baby's white bassinet, 11 of which had been

sold for $7.50 apiece at the

Kelly, meanwhile, had

begun his own volunteer mission. Nearly each day before or after work, he would

spend two or three hours in hospital records departments and unheated

warehouses, sifting through badly organized maternity files. All babies'

footprints are recorded at birth; if the boy had been born anywhere in this

area, Kelly reasoned, his footprints would be on file somewhere. The

police department couldn't pay the overtime for such a needle-in-a-haystack

search, but that was okay. The way Kelly saw it, the boy's murder was a crime

almost beyond imagination, but his being robbed of an identity was a crime

against the very order of things. Everyone deserved a name. Perhaps Kelly would

be able to set things right again.

|

|

|

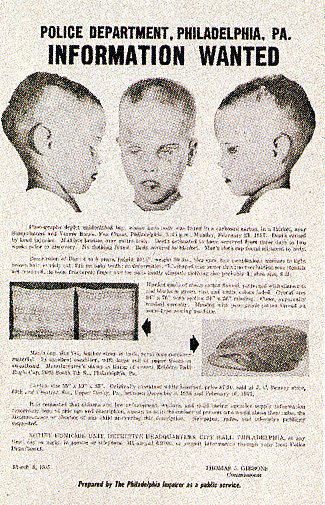

Investigator Remington Bristow reads a prayer at the 10th anniversary of the boy's discovery. |

"Good luck, hon -

maybe today you'll get a winner," Ruth would tell Kelly as she kissed him

goodbye each morning. When he returned home at night, she'd shoot him an

expectant look, and he'd wordlessly shake his head no. In the hours between,

Kelly would go through the same routine over and over again: pulling a set of

prints from a folder, laying them flat beside the boy's footprints, then

staring hard at the images. Sometimes he could tell at a glance that they

weren't a match, while others required close scrutiny through a magnifying

glass. Occasionally the prints were nothing but an ink splotch, impossible to

read, and Kelly would despair: Is that you? When his enthusiasm flagged,

he would remind himself of Scripture: "Seek, and ye shall find."

Religion and hard science were the twin pillars of Kelly's life; he aspired to

respect both and keep them in balance. (Later in life, he would be astounded to

learn that the science of fingerprinting is mentioned in the Book of Job -

"He sealeth the hand of every man, that all men may know his work" -

thus uniting Kelly's two passions.) To cover his bases, when Kelly went to the

Good Shepherd girls' home to request adoption records for out-of-wedlock babies

born there, he asked the nun to pray for his success.

He wasn't the only

person preoccupied with the boy. A medical examiner's investigator named

Remington Bristow, a quiet man with a craggy face, had also been trying to

solve the case on his own time. Drawn together by their shared interest, Kelly

and Bristow would often meet in one or the other of their City Hall offices.

They agreed on one thing from the start: The boy's abusive parents or

caretakers must have killed him. Considering the boy's grooming, perhaps it had

happened during bath time; he'd resisted, and been smacked around harder than

usual. Certainly the four bruises across his forehead could have been dug in by

rough fingers trying to keep his head still during a haircut. Or maybe his hair

was cut postmortem, to disguise his identity.

But how to lure the

parents out of the woodwork? A year or two into the case, Bristow cleverly

planted an idea in the newspapers that perhaps the boy's death had been accidental

and his loving family had been too poor to afford a funeral. Bristow didn't

believe it, of course, but hoped to bring the killer forward. It didn't work.

Even so, Bristow's determination grew with each passing year. In year five, he

consulted a psychic, which raised some eyebrows. In year six, he offered a

$1,000 reward from his own meager salary for any information leading to the

boy's identity. To observe the 10-year mark, Rem Bristow organized a

Christmastime cemetery visit with a group of ME investigators. Bill Kelly still

cherishes a black-and-white picture taken that snowy day; it's in his white

binder. The group is crowded around the grave, an American flag flapping behind

them; Rem's expression is grim as he gazes down at the little boy's headstone.

Poor Rem. Somewhere along the line, Kelly learned that Bristow had a daughter

who died in infancy, of crib death. Maybe that explained some things.

As for Kelly, after nine

years of poring through maternity records, he finally ran out of records to

search. It had taken him countless hours - time he could have been earning

extra cash as a shutterbug, or spending with his family. At least some good

came of it, Kelly consoled himself: He became so well-known to the hospital

staffs that he'd been called in to resolve a couple of delivery-room mix-ups.

Could that have been the divine reason he'd been set on this case? If he

couldn't find the boy's identity, maybe he'd been meant to restore the

identities of those other little boys and girls. Kelly tried to find comfort in

that notion. But he was deeply bothered by his defeat, and by a memory that had

disturbed him throughout his years of searching. Four months after first

visiting the nun at the Good Shepherd home, he'd gone back for a follow-up,

bearing a box of Whitman's chocolates.

"By the way,

Sister, did you say a prayer for me? Because I'm still searching," Kelly

had said, half-joking. He was frozen by her response.

"Oh, every day, Mr.

Kelly," the nun had answered serenely. "Maybe God said no."

A person can't go

through all that Bill Kelly has - four years at war, first on a destroyer in

WWII and then on the ground in Korea; 16 years with the Philadelphia police

department, and another 15 with the adult probation department - without some

things sticking with you, and not in a good way. Bill Kelly'd probably be on

the funny farm by now if he hadn't found an outlet for his disquiet: He spends

one long weekend each year in silence at the

The hairs on Bill

Kelly's arms stood on end. He'd heard that a couple of retired guys his age had

revived the case: a detective named Sam Weinstein, and a guy from the medical

examiner's office, Joe McGillen. Could they actually have done it? Kelly sank

into his armchair and waited impatiently through a commercial.

He had never forgotten

the boy. No one had, it seemed; each time Kelly visited the grave, it was

strewn with flowers and toys. Some were from other investigators, but most were

left by regular citizens, prompted by some shared sense of loss. Maybe they

truly grieved for the boy; then again, perhaps he had become a symbol in their

minds, away of giving shape and expression to their individual sorrows.

Sometimes Kelly wonders whether that was the boy's purpose, that he was

meant to be a tragic reminder of the fragility and helplessness of little

children. Kelly would always murmur a prayer at the grave: "Guide me where

to seek, that I may find the identification of the little unknown boy. Or, as

I've come to call him, Sean." Then, mindful of the Good Shepherd nun, he'd

add, "Thy will be done." Sean was a good Irish name, just for use

until the boy's true name surfaced. Oddly enough, when Kelly's daughter Eileen

became pregnant with the sixth of his 10 grandchildren, she told him she

planned to name her baby Sean, a coincidence that had startled Kelly. Sean is

17 years old now, president of his class at Father Judge.

Maybe the elderly

detectives working the case had found the answer. But as the news flashed a

black-and-white picture of a boy with a bowl haircut, Kelly was overwhelmed

with disappointment.

"I know who that

is," he told Ruth heavily. "I already identified him."

They'd been so sure of

that lead back in '65. He and Bristow had brainstormed that since the boy had

no vaccination scars, perhaps his parents had lived under the radar, were some

sort of itinerants. For a while, they'd turned their attention to a family of

carnival workers. Then they considered that maybe the boy had been a recent

immigrant. Going through newspapers, Kelly came across a 1956 article about the

tide of Hungarian refugees - and there, in the accompanying photo, was the

little unknown boy. It had to be - the ear looked just like his. With

the assistance of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Kelly sifted

through 11,200 passport photos before finding the Hungarian boy's picture, and

located his family in

Well, it seemed that the

investigators going through the old case file had come across that same photo,

and got a little excited, and put it on TV. Kelly phoned the police department

the next morning to set them straight. "I heard you were dead!"

homicide detective Tom Augustine exclaimed. Kelly just laughed: "Rumors of

my death have been greatly exaggerated." He unearthed his box of files

from the basement, and he and Sam Weinstein and Joe McGillen met for coffee at

a diner. And just like that, Bill Kelly was back on the case.

It didn't take long to

bring him up to speed. After Rem Bristow's death in 1993, with the

investigation still open but no one manning it, the Vidocq Society - a group of

local investigators devoted to solving old murder cases - had suggested

Weinstein and McGillen get on it. Their point person within the police

department was Detective Augustine, who'd been but a boy himself when the Boy

in the Box was murdered and never forgot the mutilated face on those posted

flyers.

There was one danger

Kelly was aware of as he plunged back into the case, one that Rem himself might

have succumbed to: wanting an answer too badly, believing in a certain

resolution despite its shaky logic. Bristow had grown more obsessed with each

passing year. One time, while on vacation in

Kelly had nodded along

with Rem's theory, but was rather taken aback. It was as though Bristow had

gotten too close to the boy, until he couldn't bear the idea of intentional

harm coming to him. It seemed clear that he was bending the facts to fit his

theory - after all, a bassinet and a pond do not a case make. Besides, the

police records showed the children at that foster home were accounted for.

Perhaps all Rem really wanted by that point was a resolution, any

resolution.

In 1998, though, there

was new, hard science to pursue: The Vidocq Society arranged for the little

boy's skeleton to be dug up for DNA testing. At the exhumation, Weinstein was

struck by the disgraceful state of the boy's grave in the potter's field in

Holmesburg, littered with condoms and beer bottles and Kotex pads. When it came

time to rebury the boy, they decided to give him a little more dignity;

By the time Bill Kelly

joined up in '99, the elderly investigative team had its hands full. The

reburial had attracted lots of attention, including a segment on America's

Most Wanted, spawning dozens of leads for Weinstein, McGillen and now Kelly

to follow up on. They turned out to be nothing but nebulous recollections,

viewer suggestions ("Did you check with hospitals?"), and nut jobs

who sent drawings of what the "cult" had done to the boy. The DNA was

a wash, too; they had a sample, but no one to match it to. Then Sam Weinstein

fell ill, leaving Kelly and McGillen to work the case on their own. Hoping for

inspiration, they managed to locate the crime scene - a challenge, considering

how the lush, green Fox Chase of 1957 had changed. The patch of wooded ground

where the boy once lay is now just to the left of someone's driveway, by the

side of a wide paved road lined with brick homes; Kelly and McGillen were only

able to find it thanks to a telephone pole that was still across the street.

Standing there amid the whizzing traffic, Kelly thought about how much the

world had changed through the years, and yet how little the case had. How were

they supposed to name the little boy now? It seemed hopeless. Maybe the nun was

right. Maybe Kelly wasn't meant to find the answers.

|

The Fox Chase discovery site in 1957. |

PAVED OVER: The same site today. |

And then. And then.

The morning of

With the psychiatrist

acting as a middle-man, the investigators began a two-year correspondence with

Mary, slowly piecing together the details. She claimed to have grown up in

After such a long

drought, Bill Kelly and Joe McGillen were ecstatic at this new stream of

information, even if it was slightly bizarre. They rushed to verify the

details as each fragment was revealed, nearly giddy with urgency. When they

received a letter the day before Palm Sunday 2002, mentioning the name of

Mary's childhood street, the pair couldn't wait; as soon as Mass let out, they

drove to Lower Merion, still in their church suits, knocking on doors until

they confirmed that Mary's family had indeed lived there. At long last, in June

2002, Mary agreed to a face-to-face meeting. Because of McGillen's fear of flying,

they rented a van for the trip to Ohio, with McGillen driving, Tom Augustine

riding shotgun with the directions, and Kelly with his legs up across the

backseat for his circulation's sake.

It took Mary three hours

to tell the whole story. She was 12 when it happened. She remembered the boy

had thrown up after eating some baked beans. She remembered her mother, enraged

at the mess, throwing the boy in the bathtub and then beating him, slamming his

head again and again against the bathroom floor. The boy let out a shriek, the

only sound Mary ever heard him utter. Then he was silent. Her mother cleaned

him up, cut his untended hair, wrapped him in a blanket, and carried him out to

the trunk of the car. Mary went with her, wearing her raincoat against the February

drizzle. She remembered driving to a forlorn place, getting out and standing by

the trunk. Her mother stiffening as a man stopped his car: "Do you need

any help?" Her mother shaking her head no. After the man drove on, her

mother stashed the dead boy in an empty box lying nearby. Mary had memorized

the route home, so that one day she could return for him. He wasn't her real

brother, but she loved him all the same.

The investigators were

rapt. What was his name? they asked hungrily.

|

|

|

STILL SEARCHING: Kelly, left, and

other investigators at the boy's grave in |

It comes down to this, an

old man standing over a boy's grave. Bill Kelly is at ease here. He brushes

some twigs from atop the headstone, crouches to straighten out a small flag

someone has poked into the ground. As always, there's a new batch of toys

around the stone: a soldier figurine, a race car, a ceramic teddy bear, a

couple of plastic orange fish that are probably bath toys. Flowers, too - the

Ivy Hill manager says that when people come to visit a loved one, they often

pause by the boy's grave and pull out stems from their bouquets. Kelly once

left a green ball belonging to his grandson Sean, thinking that if Unknown Sean

were alive, he'd probably like to play with it. Kelly visits twice a year,

usually. He'll be back again on November the 11th, when the Vidocq Society sponsors

a memorial service to commemorate five years since the boy's reburial.

Kelly and McGillen have

corroborated everything of Mary's story they can. They traced the route she

described, and found it indeed leads between her

That frustrates Kelly.

Of course Mary had mental problems - who wouldn't, after the things she

witnessed as a child? But he wearily accepts that there's further work to be

done. Not that he doesn't have other things to do with his golden years, mind

you. He lives a good life. His days are filled with church activities, meetings

of his various clubs, joyous visits with his grandchildren - everyone calls

them "Kelly's Angels," and they in turn call him Pop-Pop - and

too-frequent doctor appointments. But Kelly always finds time to spend a few

hours each week going through his notes, flipping through his binders. He and

McGillen have worked up an extensive genealogy of Mary's family in the hope of

finding other living relatives. They've come up with yearbook photos of Mary's

parents, and interviewed one of her mother's former co-workers. They tracked

down and reinterviewed the Good Samaritan. Kelly and McGillen feel Mary is

telling the truth. Bill Kelly looked her in the eye, and he firmly believes

her. What choice does he have, really? Because if not this answer, what then?

Kelly understands now

why Rem came to believe his theory about the foster home. Maybe sometimes what

we call truth is simply the answer we choose to live with, a way to reassure ourselves

that we've done all we can. In the end, maybe we all want to believe in something,

even if we can't quite connect the dots, even if it's a belief in something we

can't see. Maybe it all comes down to faith. Bill Kelly wants to have faith in

Mary. He wants to have faith that the answers are close at hand, and that he

will finally do right by this little boy. And he wants to have faith - in

faith.

Perhaps it comes down to

accepting that sometimes, life doesn't match up neatly like the loops and whorls

of a fingerprint. In time, Kelly is sure he'll find the true answers to the

mystery of the boy's identity - if not in this life, then in the next. And so

maybe he has found a set of answers he's willing to live with, for now.

Bill Kelly lingers at

the grave for a moment longer, then touches the headstone with an affectionate

palm.

"Goodbye,

Jonathan," he says gently. "I'll see you again soon.�

� 2003 Philadelphia Magazine.� Reproduced with permission.

![]()